Music and Mise-en-Abime in Three Irish Films

by Martyn Brady

“In a work of art, I rather like to find transposed, on the scale of the characters, the very

subject of that work. Nothing throws a clearer light upon it or more surely establishes the

proportions of the whole…”- Andre Gide, journal entry, 1893.

Mise-en-abime, according to film scholars such as Susan Hayward, is a “film within a film.” A classic example of this technique is a scene in which the films characters go to watch a movie in a cinema. What they view on screen is often linked with the storyline of the protagonists. For example, in Into the West (1992) Oise and Tito are obsessed with Western movies and thus what they watch on television and in the cinema are often Westerns or contain elements of this genre within them, such as when they watch Back to the Future III (1990). Mise-en-abime has been used in film practically since its beginning. From Uncle Josh Goes to the Motion Picture Show (1902) to more modern films including Roma (2018) and Inglorious Bastards (2009). And yet, the earliest description of the technique dates back to 1893, two years before the birth of projected motion picture. In this blog series I will be delving into three Irish films which use mise-en-abime in creatively based on my final year film studies dissertation. The films are: Into the West (1992), The Butcher Boy (1997) and Mickybo and Me (2004). Further reading and IMDB links can be found below. In this blog I am going to explore the use of music and mise-en-abime in these films.

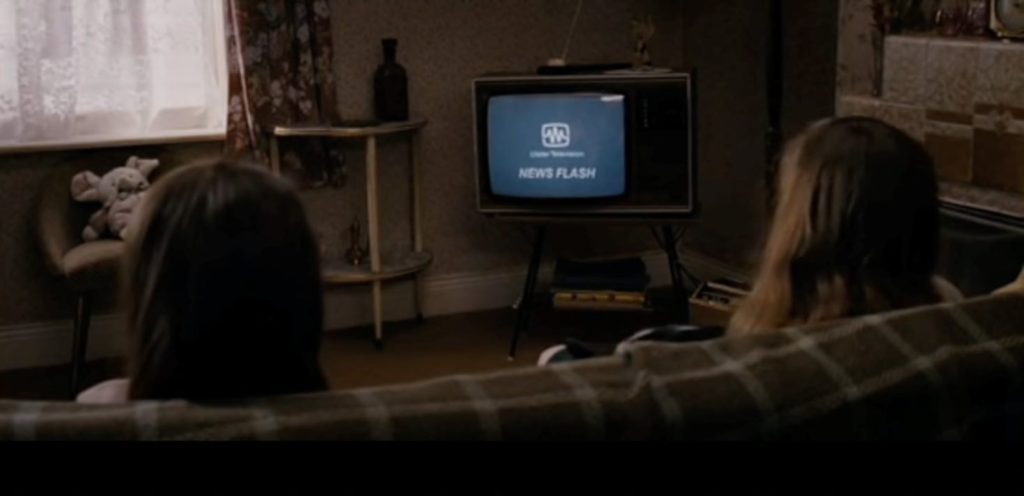

In Into the West Oise and Tito break into a cinema to take shelter from the police and the driving rain. They watch Back to the Future III. We hear the music of the film the before we see images from the movie intercut with the boys and the horse watching the show. Similarly, in Mickybo and Me, Mickybo’s parents are interrupted in their watching of The Adventures of Mr Ed by an urgent news report that the two boys are missing. We only hear the theme tune from the television show before there is a cut to the report. The Butcher Boy has the most striking example of music connected to the use of mise-en-abime. In one scene, Francie and his father Benny watch The Lone Ranger on television and the latter plays the theme tune of the show on his saxophone in perfect sync with the opening sequence. Music in film can be broken into two broad categories: diegetic and non-diegetic. The latter is music that only the audience hears and is often used to involve us more emotionally in the story. For example, a sad piano score is used when there is a death scene. Diegetic is music that both the characters. in their world and the audience themselves can hear. The examples mentioned above such as Benny playing his saxophone to The Lone Ranger are diegetic.

The use of diegetic music means that there is a solid connection between the characters and mise-en-abime. As the above quote by Gide indicates, there should be “on the scale of the characters, the very subject of that work” in other words a connection between the characters and what they see on screen. They watch the movie or T.V show, hear the music and even play the theme tune themselves. Thus, the strength of the connection ensures that the mise-en-abime stays true to how Gide originally envisioned this narrative device. Adding sound to the mix arguably strengthens that connection even more. Because the audience in the scenes mentioned also hear the music before seeing the films and the fact that they are theme tunes gives you a hint as to what the shows are. We might for example either recognise the theme tune or want to find out what the show is because of this. This arguably makes us more immersed in the world of the story as the audience is given a chance to discover what the characters are watching.

When I was writing my dissertation, I found that there was a connection between mise-en-abime and music in these films. In the small amount of literature that I found on the technique in film, I never uncovered any mention of music. I feel that exploring the relationship between music and this narrative device is significant not simply because mise-en-abime maintains a connection between it and the characters through the music. It also shows that we do not necessarily need a non-diegetic score to make the audience involved in a movie. Diegetic music can do the same thing and there are many other ways in which an audience can be involved with a narrative. Imagine then what we could do if we experiment with music and mise-en-abime. Not every filmmaker will have the budget to clear Back to the Future III for use in their film so why not, as one possibility, make a fake film or television show? In my next blog I will be exploring further what Gide originally believed mise-en- abime to be and how these three coming of age films implement the technique.